by Mary W. Walters

Polly Prewitt was a perfect parent, or as close to one as any human being can reasonably expect to get considering the materials parents have to work with. She’d suspected this for many years, although she was careful not to speak of it to anyone, including her husband, for she was also sensitive to other people’s feelings. But it gave her a certain satisfaction to know that her children would be far-better-adjusted adults for having been raised by as conscientious a parent as she.

When friends discussed their children’s bed-wetting problems, she gave little clicks of sympathy and quietly savoured the fact that her boys had both been trained before their second birthdays, and without a single tear or relapse. When other people mentioned the abysmal eating habits of their offspring, Polly gently let it be known that her boys ate what she gave them or did not eat at all. She made no fuss about it with them, she said, and they ate: spinach, tofu, the whole works.

Polly nurtured her pride by reading covers of magazines in stores. “Are you passing on gender stereotypes to your children?” Nope, she mentally responded. Her husband William did the dishes every other night and made dinner for them all on Sundays. Polly had taken a course in automotive mechanics specifically so the boys would never get the idea that Mothers Cooked and Fathers Fixed Cars. And she had not said a single word against it when Ricky demanded a doll last summer. She wrote it down on her list and bought it for him at Christmas; that way he learned he did not get everything he wanted at the moment he asked for it. It was a cuddly doll, a male baby doll, anatomically correct. The fact that by Christmastime Ricky was in kindergarten and refused to play with it – the other little boys had told him that dolls were for girls – was beside the point.

Jamie had learned that One Takes Responsibility for One’s Actions when he kicked the front wheel of his bicycle off centre in a fit of temper and could not ride it until he’d saved enough from his allowance to pay for the repair.

Her boys were in good shape, she thought cheerfully. And so was she.

And then one day she was standing in the checkout line at Safeway, frowning to herself at the boxes of sugar-coated cereal in the cart of the woman ahead of her, when a brightly coloured magazine caught her eye. She looked up. There, in bold red letters on the cover, was a question that stopped her cold.

“Has your child learned to deal with loss?” it said.

Loss? Loss? She’d never even thought of that, and here was Jamie almost nine and Ricky already past his sixth birthday. She snatched a copy of the magazine and tossed it, front cover down, into her cart.

She read the article covertly before the boys came home from school. She read it twice. The writer urged her to allow her children grief in little ways, so they would be better able later to handle major loss. A pet, the author said, is a perfect medium for teaching such a lesson.

“Do not ever attempt to replace a pet until the grief has been worked through,” the article advised. It went on to point out the identifiable stages of grief: denial, anger, finally acceptance.

Polly’s boys had missed all that, and she would certainly need to set the matter right. What if something terrible happened to her or William or, God forbid, to any of their school friends, and she had not prepared them for it?

All right. A pet, she thought, as she watched Ricky and Jamie brush their teeth that night, before she read them their story. Jamie preferred to read to himself, but she insisted. She knew that reading aloud fostered closeness between parent and child.

A dog would be too much trouble, she decided, and by the time it was ready to teach its lesson in grief, the boys would probably be living elsewhere, attending university or sweeping streets. (Whatever life course they chose was fine with her.) A dog, or a cat, would simply take too long.

Polly couldn’t stand rodents, so mice were out, and birds could live for years.

“Fish!” she said, firmly closing the book in the middle of a chapter.

“What?” said Ricky.

“Nothing” said Polly, opening the book again.

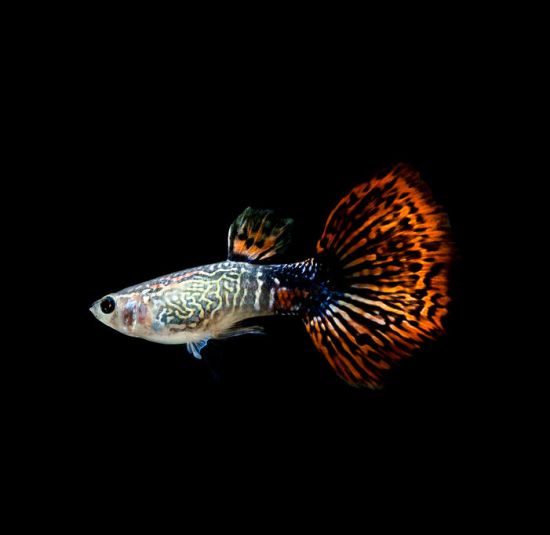

Next day, when their father had taken them to swimming lessons, she went to Sears and bought a big glass fishbowl and a guppy that looked suspiciously pregnant. She bought fish food and received instructions in the care and feeding of fish. She did not admit to the salesclerk that her intention was for the fish to die. In fact, she knew she wouldn’t be able to help sustaining its little life for as long as possible. Polly was an honourable woman.

The boys were delighted with her offering. The bowl was given a position of prominence on the coffee table in the living room. Ricky and Jamie watched the little brown being swim around for hours on end. Ricky asked at one point if he could take it out and play with it, but Jamie told him that fishes can’t live outside the water. Ricky didn’t want the fish to die, did he? Ricky solemnly said, “No.”

Polly looked on, approving.

She did not tell William of her plan because he’d only ask her at breakfast how her “ghoulish death experiment” was coming along, or words to that effect. He was capable of ruining everything when he didn’t understand her motives, and she had suspicions he would not understand them this time. There are things a parent has to do alone.

Polly changed the water regularly and fed her little charge, and it thrived. After a week or so, the boys lost interest in it, and so she gave it a name to foster their feelings of warmth and attachment toward it. “Jean,” she called it, a suitably androgynous name. The guppy had not yet produced any little guppies (which would have been a bonus: two lessons for the price of one), and William said all fish were rounder in the middle than they were towards the ends. She let the boys feed it, but even that bored them rather quickly, and they told her that since she’d bought it, she could feed it. Responsibility for one’s actions coming back at her.

______

Polly had almost decided that Jean would become a permanent part of the household, and a permanent addition to her daily routine, when she went downstairs and found him/her belly up.

Polly sighed and, her expression appropriately mournful, went up to tell the boys.

“I have some bad news for you,’’ she said when she went into their room. “Our little Jean is dead.” (“Tell them the truth!” the article admonished. “Do not tell them the creature has gone to sleep or gone to heaven. Be honest!”)

“No kidding,” said Ricky, and he began to hum the Oscar Mayer song as he pulled his pyjamas off.

“Can I see it?” Jamie asked.

That was better. “Let them see the body of the pet,” the article went on. “Let them confront their grief, hug the pet and cry.” Hugging was out, but the principle remained.

“Of course. You both can.”

She led them down to the living room and stood back to observe their reactions.

“Hm,” said Jamie. “What’ll we do with it?”

“We can bury it out in the garden, if you like. Together. The three of us.”

“Great!” Ricky said, and he ran off, half-clad, to get his shovel from the sandbox.

“Naw. I’ll be late for school and I promised I’d bring the soccer ball. Let’s just flush it.”

So Ricky and Polly buried the little bit of fish, and Jamie left for school. (Denial, Polly thought. He’s not confronting this issue. It takes time to come to terms with loss.) Ricky seemed more interested in a worm his shovel had unearthed than in the farewell to Jean, but Polly was satisfied. At least he had been present.

She waited for the boys’ reactions, but they never once mentioned the death of the fish. At last she took the fishbowl, clean and polished and very empty-looking, and she put it on the kitchen table to emphasize their loss. It was cruel, but it had to be done.

“Can I have it for an ant house?” Jamie asked.

“No! I want to collect bugs to keep in it,” Ricky said. “How come he always gets everything?”

Ants. Polly turned the possibility over in her mind. At least Jamie would have a commitment to his ants. He’d wanted them, and the loss would be greater for his having been the instigator. Ants it would be.

“Well, Ricky,” she said. “Jamie spoke first this time, and I’ve told you often enough before that life’s not necessarily fair.” She looked at Jamie. “Go ahead and start your ant colony, but I’m going to carry this out on the sun deck. I won’t have them in the house.”

It took less than a week for all the ants to escape, and they did not seem to have set up any domestic arrangements in the bowl at all during their brief stay. Polly found Jamie on the sun deck after school one day, staring glumly at the pile of dirt he had poured from the fishbowl onto the indoor/outdoor carpet. She did not mention the mess. He had enough to deal with, poor little tyke, having to confront all of this so early on in life. But it was good, she thought, as she saw a tear roll down his cheek.

She went out and sat beside him. “Do you want to talk about it?” she asked.

“I feel sick,” he said.

“That’s the sadness, dear. Nothing lasts forever, you know. All things must go away or die at some time or another.”

“No, Mom. That’s not it. My stomach hurts,” Jamie said, and then he threw up on the lifeless anthill.

It turned out to be chicken pox, and he was home for a week.

_______

“Now, bugs!” Ricky clapped his hands when he saw the fishbowl sitting clean and once again empty on the kitchen table.

“All right. But this is your last chance.”

“Last chance for what?” asked William, looking up from a forkful of shepherd’s pie.

“Oh, nothing. I’m just tired of pets, that’s all.”

Ricky collected a ladybug and two little green things and a fly before he, too, was stricken with chicken pox. He’d covered the top of the jar with a piece of plastic wrap with holes poked in it and thrown in a leaf or two for food. He’d given each bug a name and spent a long time watching his captives in the bowl. He’d left them on the sun deck when he began to feel unwell.

One morning, spotted but recovering, he recalled his menagerie and went downstairs to find them dead.

“Humph,” he said and went back to bed, leaving Polly to rinse the bowl once more.

In the afternoon, she found a piece of paper on which Ricky had written his name backward. Reversed writing was, she knew, a sign of deeper problems. Ricky was reacting. She leaned the paper against the empty fish/ant/bug bowl.

“Tell me why you did this” she asked him gently when he came down to supper.

“Did what?”

“Wrote your name backwards. Did you notice you had done it?” Ricky shrugged. “Jamie bet me a nickel that I couldn’t.”

“That’s it! I’ve had it!!” Polly, the almost-perfect parent shouted. She ran downstairs and wrote a caustic note to the perpetrator of the nonsense in the magazine.

“Loss” she noted in conclusion, “is not a big problem for well-adjusted kids. If everything else is going smoothly, they do not react to it at all.”

She felt better then, almost restored, and she went back to the dinner table.

“You’ve been awfully tense lately,” William said as she carried her plate to the sink and submerged it in the soapy water.

“I just got a little carried away with something,” she said. “It was no big deal. As I’d suspected, everything around here is just fine. And I,” she said, lifting the empty glass bowl into the air, “am turning this into a terrarium.”

“What’s a… ” Jamie said, as the bowl slipped from her hands and smashed to smithereens on the kitchen floor.

There was a stunned silence as the four of them studied the remains of the bowl.

Then, tumult.

“What d’ja do that for?” Jamie shouted. “I wanted that bowl to keep my rock collection in.”

Ricky started to cry. “I wanted to get a turtle.”

Polly stared at them in astonishment. “Keep your voices down, you crazy kids,” she said. “It’s just a bowl. I can get another one tomorrow.”

She stopped and watched their shuddering shoulders and listened to their sobs.

Then she said quietly, “No, I guess I can’t,” and went to get the broom.

(c) Mary W. Walters. Originally published in Chatelaine magazine. Also published in Cool, a collection of short stories by Mary W. Walters, River Books (2000).

You must be logged in to post a comment.